***

In today’s part of the series about lesser-known or even well-kept converts, we will talk about a very specific group within this species. Their motivation, from the point of view of many of today’s observers of the crisis in the Catholic Church, who are inclined to easy and superficial solutions (see for example Rod Dreher), can appear confused and ill-conceived. After all, according to the common opinion of contemporary followers of ecumenism, the Orthodox Church differs from the Catholic Church only in that it does not recognize the office of the Pope, or even according to Russophiles or Slavophiles, the contemporary Orthodox Church is in much better condition than the contemporary Catholic Church.

With the first one, we can first say that the Catholic Church differs from the Orthodox Church primarily in that it is – true. The Catholic Church is the Church that was founded by Jesus Christ, the Son of God and continues unbroken to this day. The Orthodox Church in the so-called It separated the Great Schism from the Catholic Church and exists outside of its communion. However, it is not only a matter of separation from Rome. The Orthodox Church has adopted many heterodox elements during the centuries of separation so that in its case it is no longer just a matter of the notorious “non-recognition of the Pope” or the dispute over the word ” filioque “. Suffice it to mention for illustration at least the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, which the Orthodox Church does not recognize. It should also be mentioned, for example, its recognition of divorces, under certain circumstances.

Others who adore the Orthodox Church as an oasis of tradition and as their easy escape from the crisis in the Catholic Church should be reminded that the Church is a timeless institution and its teaching is the Truth revealed by God, while this teaching has the fullness of all the means of salvation for almost two thousand years. The fact that nowadays many members and representatives of the Holy Apostolic and Catholic Church distort or even deny this Truth cannot change the fact that it is the Truth and the only way to salvation.

The actions of Catholic conservative admirers of the Orthodox Church are reminiscent of the reaction of a mathematics student to a professor who teaches the subject badly, and in response to this confusion, the student instead of learning the correct procedure, despite the professor’s mistakes, resigns from mathematics as such. He will be satisfied with guessing the result, happy that until he worked on the correct result under the professor’s guidance, he hit something by guessing. However, the solution is to learn mathematics correctly, which is independent of the existence and mistakes of one professor.

Of course, no one will deny that the preservation of tradition in the Orthodox Church far surpasses all Protestant and apostate sects. However, it is all the more important to understand what led Russian converts to the Catholic faith to convert. It was not the beauty of the ceremonies, nor the antiquity, but the Truth of the Faith, the certainty of the dogmas and the historical credibility of what the Catholic Church proclaims. These converts deserve our admiration more than converts from dull and dry Protestantism, or even from the folly of pagan idolatry. At first glance, it seems that the Catholic Church did not give them much more than what they already had. However, their search had to focus much more intensively on the essential, what lies behind the beauty of the liturgy and the treasure of tradition, what distinguishes the Orthodox Church from the Catholic Church – the Truth.

Sofia Petrovna Svečina – owner of the conversion salon

At the time when the Russian nobility began to think about dealing with the Catholic faith at all, that is, at the beginning of the 19th century after the Napoleonic wars, the fiasco of the French Revolution and at the time of the conservative Catholic revival, framed by figures such as Joseph de Maistre, René de Chateaubriand or Louis de Bonald, became the first known convert from the homeland of St. Vladimíra, daughter of Russian State Secretary Peter Alexandrovich Sojmonov.

source: Wikimedia commons

She was born in 1782 in Moscow and from childhood showed a deep talent for acquiring a broad education. She acquired an excellent knowledge of the main European languages (Italian, English, French, and German), while her knowledge of the classical languages was also excellent: ancient Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. As the daughter of a leading noble family, she became a lady-in-waiting to Empress Maria Fyodorovna.

At the age of seventeen, at her father’s wish, she married the much older military governor of St. Petersburg and General Nikolai Sergeevich Svechin, a widower who was already 42 years old at the time. The marriage did not deviate from the framework of noble marriages of the time and was relatively happy. However, soon after the marriage, her father as well as her husband found themselves in the disfavor of the mentally unstable Czar Paul I, as a result of which the father died of a stroke and the husband had to resign from his office.

Young Sofia, who could not have children of her own, but lovingly cared for her adopted daughter, under the pressure of these family and personal dramas, plunged into her inner world, becoming an even more avid reader, devouring Western literature and philosophy, so fashionable in the times salons of the Russian nobility. In one of these salons, Sofia fatefully meets a well-known French emigrant, a refugee from the horrors of the French Revolution and, most importantly, an ardent Catholic, Chevalier d’Augard. His captivating presentation and apology of the Catholic faith dug deep into Sofia’s soul, so much so that she began to search for members of this small French diaspora in Russia.

In this search, she finally came into contact with the famous Joseph de Maistre, who at that time was working in Russia as the ambassador of the monarch of the Kingdom of Sardinia. His influence in the circles of the Russian nobility at the time went so far that Tsar Alexander I himself began to openly sympathize with Catholicism. At that time, in the eyes of the Russian nobility, the Catholic faith was stripped of its forbidden fruit, and soon the first conversions appeared in these circles.

Sofia’s was neither light nor short. She was plagued by doubts and could not make up her mind for a long time. However, in the end, an event that decisively put an end to the Russian nobility’s flirtation with Catholicism probably helped her definitive conversion. Under the pressure of the Orthodox hierarchy, the government decided to expel the Jesuits, who had been tolerated until then, in order to persuade the Russians to convert to the Catholic faith. Faced with the threat that she too would now be condemned by society for her faith, perhaps Sofia realized her duty to God and openly confessed her sympathies towards the Catholic Church.

Czar Alexander, who had previously also made no secret of his sympathies for Catholicism despite signing the decree to expel the Jesuits, maintained his favor with Sofia. However, the rest of society did not, so she decided to emigrate to Paris in 1816, where she definitively and officially accepted the Catholic faith. In Paris, her salon soon became a sought-after place where French celebrities of the time met and where many conversions from among the Russian nobility took place. Her captivating personality and even more her gift of conversation, which Lacordaire attributed to her as “the great master of conversation”, together with her intelligence, education, and zeal for the Catholic faith, formed a most attractive mixture that led to salvation many a wandering soul.

In her salon, such aces of the French education of the time as Abbot Félix Dupanloup, Alexis de Tocqueville, Paris Archbishop Hyacinthe-Louis de Quélen, Prosper Guéranger, Victor Cousin, or her compatriot, Prince Ivan Sergejevich Gagarin, were frequent guests.

Thanks to her and in her salon, Countess Sofia Rostopčinová, another Russian convert and later French writer, author of the famous children’s books Sofia’s Troubles, Somárik’s Memory, and Little Good Girls , met her future husband, Count de Ségur.

She became a permanent part of French literature thanks to her rich correspondence with the intellectual elite of the time. Her correspondence with Alexis de Tocqueville, Count Fréderic de Falloux and Viscount Armand de Melun stands out.

Sofia Petrovna Svečina died in Paris in 1857, and her reputation as a defender of the Catholic faith was so great that shortly after her death rumors spread about her canonization. And even though it did not happen, and even if she still had to atone for some sins in Purgatory, it is likely that the prayers of the multitude that she converted to the true faith shortened her temporary suffering and now she is enjoying with them in Heaven.

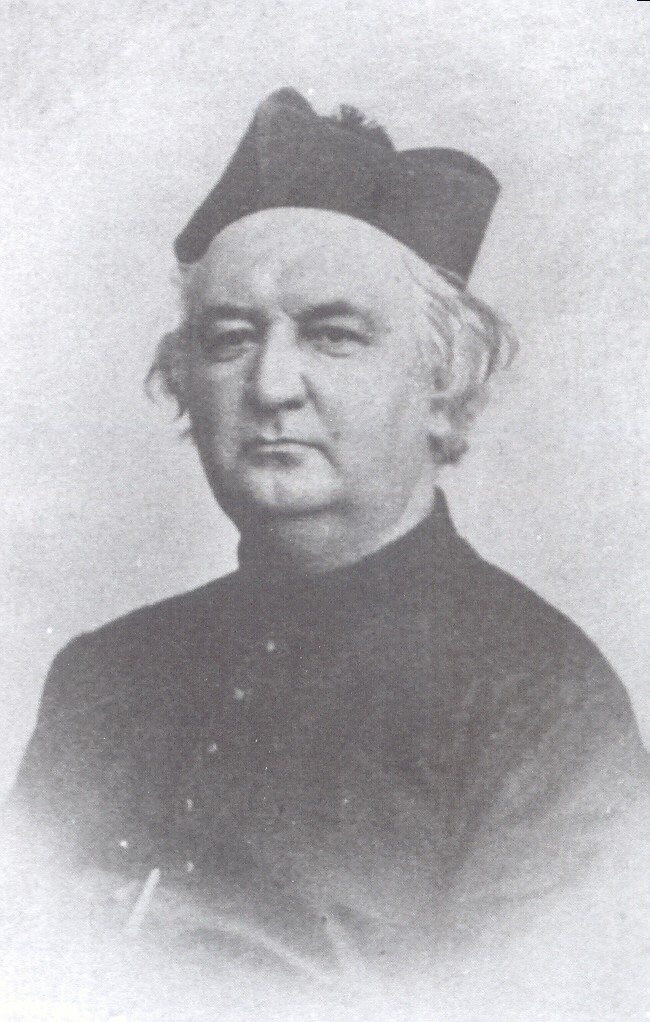

Vladimir Sergejevich Pecherin – from a nihilist to an Irish priest

The person and especially the life of the poet Pečerin are significantly more bizarre than the ultimately peaceful life of Sofia Svečina in the Parisian salons. He was born in 1807, when she was already enchanting the cream of St. Petersburg, at the very opposite end of Russia, in seaside Odessa.

source: Wikimedia commons

The son of a cruel nobleman, who regularly beat not only the servants, but also his wife, Vladimir’s mother, was very sensitive to this cruelty and concluded it that questioned not only the traditional world of tsarism, family, and order but also Christianity itself. In his later memoirs, he described his father’s rage as follows:

“ I can still hear their wails as he whipped them in the stables. My mother sent me to my father to intercede for Vaska or Jaška. I cried, begged, kissed my father’s hands and sometimes mitigated the cruelty of their Russian fate… But my mother was also a victim herself… Once she took me by the hand, led me to a corner, told me to kneel next to her in front of the icon of St. Nicholas, and in tears said : “Oh, Saint Nicholas, you see how unfairly we are treated!” Meanwhile, in the next room, a party was taking place… But the queen of this party was not mine mother, but another woman… This other woman was the wife of our colonel, a cunning and beautiful Pole, with whom my father had an almost open affair.”

After a short career as a university professor in Moscow, he became a nihilistic dissident, of the kind that was numerous in Russia in the 19th century, and which the Russian novelist Dostoyevsky describes vividly in his novel Besy . He decided to emigrate to the West and wrote a personal letter to the Tsar about his decision.

In Europe, he became a member of bohemian literary groups, inclined to the same romantically tinged nihilism as himself. He made a name for himself as a poet with classicizing tendencies in his style and an iconoclastic tendency in his content. It was an even bigger shock for all his friends and acquaintances when he decided to convert to the Catholic faith in 1840.

His conversion was total and thorough. He decided to become not only a Catholic but also a Catholic priest. Tsar Nicholas I was so enraged by this news that he stripped him of Russian citizenship, nobility, and any inheritance. He was also banned from returning to Russia. However, this only strengthened Pečerin in his decision. He became a member of the Redemptorist order, whose mission was to work among the poorest of the poor. He lived in a monastery in Clapham, near London, and later in Ireland, where his oratorical skills attracted large audiences and made Pecherin’s sermons very popular.

After his departure to Ireland, he lived excellently with the mentality of the people there and even came into the wider historical consciousness of the British Empire as the last Catholic priest, tried in 1855 for violating the Protestant “blasphemy” law, that is, in fact, for questioning Protestant heresies. Pecherin, who as a local Catholic priest was at the head of the campaign against immoral literature, while burning dubious books also threw into the flames the Protestant Bible of King James I. Stuart, all this on Guy Fawkes Day, a Catholic dissident from the time of King James who was executed for allegedly planning to blow up the English Parliament. On this day, English Protestants celebrate the capture of alleged Catholic traitors.

Newspapers ran ahead in anti-Catholic hysteria, but the jury acquitted Pečerin, much to the indignation of Protestant groups. The enthusiastic Irish Catholic population in Dublin wildly celebrated his freedom and even composed two songs about him that are still part of Irish folklore. The case had a different response in Russia, where anti-Catholic propaganda portrayed Pecherin as a typical “Jesuit” blaspheme while hushing up the liberating finale.

In 1856, Pecherin was invited by Cardinal Newman to preach on St. Patrick’s Day in the chapel of the newly founded University of Dublin. There, Pečerin openly took the side of the Irish national liberation struggle. Contemporary reports praise his English and rhetoric, which were said to be the envy of even the most experienced English speakers, adding that many cried during the sermon.

In 1862, after 20 years of missionary service, Pecherin was allowed to leave the Redemptorists at his request. To save him from poverty, Pecherin was assigned by the Archbishop of Dublin, Cardinal Paul Cullen, as chaplain to the Sisters of Mercy at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital. Pecherin spent the last 23 years of his life there while living as a virtual hermit.

Although it may seem that way at first glance, he never forgot about Russia. He once wrote about his split between two worlds:

” I happen to lead two lives: one here, the other in Russia. I can’t get rid of Russia. I belong to him by the very essence of my being. It is thirty years since I settled here – but I am still a stranger, my spirit and my dreams do not wander here – at least not in the environment to which I was bound by fateful necessity. I don’t care if anyone here will remember me when I die, but Russia is a different matter. Oh, how much I wish to leave some memory of myself on Russian soil, at least one printed page that will bear witness to the existence of a certain Vladimir Sergeyevitch Pecherin .”

However, those Russians who decided to follow him in the most important decision of his life, converting to the Catholic faith, do not doubt at all about the significance of his existence for Russia. His life was a small but significant contribution to Our Lady of Fatima, at her request for the consecration of Russia.

Ivan Sergejevich Gagarin – from a descendant of the medieval nobility to a Jesuit

A descendant of the ancient Russian nobility, who belonged to the rulers of Starodub in the Middle Ages, and the son of Prince Sergei Ivanovich Gagarin and Varvara Mikhailovna Pushkinova, he was born in 1814. His origins and talents predestined him for a diplomatic career. His uncle worked as an ambassador in Munich, where young Ivan was sent in 1833 as chief actuary.

source: Wikimedia commons

Hello. And Bye.